In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Some of the best science fiction authors focused on shorter works, especially back in the days when magazines were the primary market for the genre. And unfortunately, many of those authors tended to disappear from the reading public’s attention far too quickly. One such author is William Tenn (the pen name for Philip Klass). In the days after World War II, he appeared frequently in the pages of magazines like Astounding, Galaxy, Planet Stories, and Thrilling Wonder Stories, becoming known for his wit, humor, and the quality of his writing.

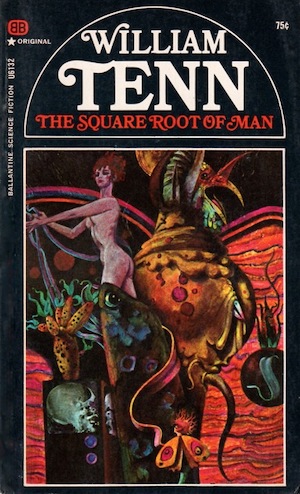

I probably first encountered William Tenn’s work in the pages of my dad’s Galaxy magazines during my youth. But the first time I remember reading his work is when the Ballantine Books Del Rey imprint released collections including nearly all of William Tenn’s fiction in 1981, which I discovered and purchased when I lived in the Washington, DC area (one of many times Del Rey reprints introduced me to the work of a great author I might otherwise have missed). I can’t recall which volume I bought first, but once I had one, I bought all I could find. They were a delight—well crafted, witty, and engaging tales that were fun to read. Tenn’s characters always felt real and fully developed. And this particular collection offers a good selection of tales from throughout the author’s career.

About the Author

Philip Klass (1920-2010), who wrote fiction under the pen name William Tenn, was an American writer and educator, known primarily for his short stories and satire (because of the similarity in their names, he was sometimes confused with the skeptical UFO researcher Philip J. Klass, an entirely different person). His parents were Jewish, and immigrated to Brooklyn, New York when he was an infant. His body of work in the science fiction and fantasy genre was small enough for the NESFA press to collect his entire output into a two-volume omnibus edition. Best known for his shorter work, he only wrote two novels during a fiction-writing career that spanned the years from 1946 to 1993.

Klass was among the more accomplished writers of science fiction, and taught writing at Penn State University from 1966 to 1988. He was most known for his humor, satire, and well-crafted prose. Theodore Sturgeon is quoted in Tenn’s Wikipedia entry, declaring:

It would be too wide a generalization to say that every SF satire, every SF comedy and every attempt at witty and biting criticism found in the field is a poor and usually cheap imitation of what this man has been doing since the 1940s. His incredibly involved and complex mind can at times produce constructive comment so pointed and astute that the fortunate recipient is permanently improved by it.

While some of Klass’ earliest stories appeared in Analog, at some point it appears that, like other authors, he began to chafe at the heavy editorial hand of John Campbell, and he moved on to other magazines. About half of his output appeared in Galaxy during the years from 1951 to 1963.

You can find a few of Klass’ short stories on Project Gutenberg, including “Venus Is a Man’s World,” one of the stories included in The Square Root of Man, and “The Men in the Walls,” a story later expanded into the novel Of Men and Monsters. And on Wikipedia, I ran across a link to a reprint of one of his last short stories, “On Venus, Have We Got a Rabbi!” That final story was one Tenn had in mind before he’d retired from publishing fiction, but remained unwritten because he thought there was no market for it…until he encountered a fan putting together an anthology of Jewish science fiction. There is also an audio link to a reading of the story by the author himself.

Humor in Science Fiction

Humor has been part of science fiction from the earliest days of the genre. Many of the early works were social satires, which poked fun at current issues by transporting them to a fictional world. The pulp magazines were fertile territory for humor, as their primary purpose was to entertain the reader. And the short stories that filled the magazines were a perfect format for delivering a good twist or a solid joke at the end. Even Campbell’s Astounding/Analog, which had a reputation for stodginess, often featured humorous stories in its pages. I’ve reviewed more than a few works with humorous content in this column, everything from books that include some jokes here and there to books whose whole purpose is to make the reader laugh. They include examples like: Bill, the Galactic Hero, The Compleat Enchanter, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon, The Stainless Steel Rat, and The Space Merchants. You can find a useful Encyclopedia of Science Fiction article on the theme of humor in science fiction here.

William Tenn’s Jewish heritage and his upbringing in the immigrant Jewish community in Brooklyn, New York were central to his work, and to his sense of humor. He was a contemporary of famed comedians like Mel Brooks (from Brooklyn), Carl Reiner (from the Bronx), and Sid Caesar (from Yonkers). The Jewish immigrant culture of New York valued cleverness and quick wit, and was fertile ground for a new brand of humor that first spread through the bars, clubs, and vaudeville halls of New York and the “Borscht Belt” of summer resorts in places like the Catskills. From there, spread by emerging technology that included radio, movies, and the new media of television, it swept the country, exerting an influence far beyond the neighborhoods that spawned it. The style of comedy these entertainers pioneered so influenced popular tastes that it shaped mainstream comedy entertainment throughout the United States—and what these Jewish comedians were doing on television, Tenn was doing on the pages of science fiction magazines. He was known for witty stories that worked well at shorter lengths, where a clever twist could elevate the narrative into something special. And on those occasions where he directly dipped into his heritage, the stories really sparkle with energy and fun.

There is an excellent Wikipedia article on Jewish humor that has not only has a comprehensive history of the topic, but also a section of examples that contains some pretty good jokes.

The Square Root of Man

“Alexander the Bait”—the first story in the book, and one of Tenn’s first published stories—was published in Astounding in 1946. In it, scientist Alexander Parks has developed a means of analyzing the composition of the moon by bouncing radar signals off the surface. Detection of precious metals spurs a rush to colonize the moon, but the colonists find themselves empty-handed. Unlike the protagonists of earlier science fiction stories, lone geniuses who build spaceships and go exploring themselves, Mr. Parks realizes that no single man can do what government and corporations can do; so, by doctoring what his radar detects, he cons humanity into exploring the wider universe.

“The Last Bounce,” published in Fantastic Adventures in 1950, looks at first like a generic space opera portraying the adventures of the Scouts of the Space Patrol. But rather than focusing on what the plucky Scouts find, it instead looks at the impact that being on the cutting edge of exploration has upon the Scouts themselves. The story turns bittersweet when a veteran scout encounters inexplicable mysteries that lead to death, and decides he has gone on his last mission.

In the delightful “She Only Goes Out at Night” (first published in Fantastic Universe in 1956), we meet a dutiful country doctor, Doc Judd. His son Steve comes home from college for the summer, but starts keeping odd hours. In the meantime, Doc has to deal with an epidemic of a strange disease, which, while not killing the patients, creates anemia and malaise. Doc’s handyman/driver is Rumanian, and begins to suspect a legend from the old country has come to America. And sure enough, young Steve’s new flame, the beautiful Tatiana, turns out to be a vampire. The young lovers seem doomed to follow the path of Romeo and Juliet until the practical Doc Judd intervenes. Armed with the tools of modern medicine, he rolls up his sleeves, comes up with a solution, and everyone lives happily ever after.

My favorite story in the collection is “My Mother Was a Witch,” from Planet Stories magazine in 1966. The protagonist describes how every adult woman in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn is a witch, making it a dangerous place for a boisterous young boy. One day, when he runs afoul of one of the oldest and most dangerous witches around and is saddled with a hideous curse, only a counter-curse from his mother can save him. In the introduction, I was surprised to find Tenn referring to this fantasy story as a memoir. Rereading it, I realized it is one of those rare stories that, instead of stretching the truth into fantasy, manages to make the real world seem like something magical.

“The Jester” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, 1951) is the story of a comedian attempting to stay on top of his game in the cutthroat business of 3D teledar in the year 2208. (Despite this future setting, however, the story feels very much rooted in the entertainment business of the 1950s.) He purchases a robot to help write his jokes, but after a series of slapstick mishaps, ends up playing second fiddle to his own robot. Oh well, at least it’s a living…

“Confusion Cargo” (Planet Stories, 1947) is a space opera story inspired by Mutiny on the Bounty. While it is primarily a straightforward tale of action and adventure, Tenn also includes a number of twists and turns that make it stand out from similar tales of that era.

In “Venus is a Man’s World” (Galaxy, 1951), Tenn turns some of the clichés of planetary romance on their head. Instead of Venus being a planet of women, it is, like other frontiers from throughout history, a male-dominated society. And Earth has a shortage of eligible bachelors. The protagonist is a boy whose older sister has booked passage on a ship full of women looking for husbands. The boy narrator, attempting to figure out the mysterious actions of older men and women, adds a humorous feel to the story right from the start. And the sister he thought was an idealist turns out to be extremely pragmatic. There are some dated ideas about gender roles here, but most of them end up being skewered by the satire.

“Consulate” (Thrilling Wonder, 1948) is the story of two ordinary guys from Massachusetts, Paul and Fatty, who go out fishing one evening only to be kidnapped (boat and all) by aliens who look like big jellyfish, and drag the two off to Mars. When they arrive, it turns out the aliens waiting there aren’t only Martians, but include representatives of some sort of wide-ranging galactic federation. It also turns out that ordinary guys from Earth can make pretty good diplomats when they put their mind to it.

“The Lemon-Green, Spaghetti-Loud, Dynamite-Dribble Day” (which appeared in Cavalier in 1967 as “Did Your Coffee Taste Funny This Morning?”) is a story inspired by reports of the CIA experimenting with releasing drugs in urban areas. The tale is told from the surrealistic and unreliable viewpoint of people impacted by the drug.

Final Thoughts

William Tenn was a fantastic science fiction writer who deserves to be more widely remembered. If you can, look up some of his stories on the internet, look for used paperbacks in bookstores or online, or order that two-book omnibus edition of his work from NESFA. You won’t regret it. His stories are beautifully crafted, and full of energy and humor, some of it laugh-out-loud funny.

I’d love to hear from any of you who have encountered William Tenn’s writing—or if you want to talk about humor in science fiction in general, I’d enjoy that as well.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.